Dear Friends and Colleagues,

I recall distinctly a conversation I had about 10 years ago, whilst working at my previous search firm, with a man who could best be described as the patriarch of executive search in Western Canada. For it was he who brought the first retained executive search firm to these parts in the 1980s. He was polished, wise and in his early 70s — think Obi-Wan Kenobi in a starched white dress shirt and navy blue suit. Walking back from the Petroleum Club (naturally) after lunch that day, he was lamenting the rise of LinkedIn and other nascent on-line tools encroaching upon, and rapidly rendering obsolete, the singular advantage he possessed over all others: his Rolodex.

For those of you under the age of 40, a Rolodex was a desktop card index used to record names, addresses, and telephone numbers, in the form of a rotating spindle or a small tray to which removable cards were attached.

form of a rotating spindle or a small tray to which removable cards were attached.

For Obi-Wan, his Rolodex was the Crown Jewel; his shield to fend off all comers and his sword, adorned, like so many brooches and charms, with the contact details of every executive in town. To have his Rolodex was to be King. And the King ruled for decades, unperturbed by others, his ransom having finally been paid by Korn/Ferry nearly 19 years ago as part of an industry-altering shopping spree.

As we strolled back to the office from lunch that spring afternoon almost 10 years ago, a lunch at which I confided in him that I planned to leave the firm to start out on my own, he bemoaned the rapidly changing industry and advised against such a move. “LinkedIn, the Internet, the Facebook, the Robots”, he muttered despondently, “we’re doomed”. We stopped walking, I turned and looked him in the eye and said, “No. You’re doomed. I’ll be just fine.”

While this wasn’t quite the Duel on Mustafar (google it) (I did), it was the moment at which he realized that his treasured Rolodex, with all its countless contacts and myriad powers, was now mine, and everyone else’s too. And with that advantage neutered, and the playing field levelled, it was no longer a matter of simply finding the people – for they were found – rather, it was about something much trickier.

Indeed, today, calling it “search” is akin to “taping” a TV show or “carbon copying” someone on email. It’s a word that has hung around, notwithstanding having lost its application. For the search part has become largely superfluous. Sure, we possess a resourcefulness and sleuthing quality that enables us to dig and troll and creep more expertly than your average hacker – honing our skills, as we do, each time one of the young single women in our firm (for both men are encumbered) mentions an impending date only to be greeted the next day with a full dossier on the individual that would make Christopher Steele blanche with envy. The virtual Rolodex gifted to us by the internet is wasted if we don’t know what to do with it; and we have fully leveraged all manner of technology that allows us to compete with multi-national firms many times our size.

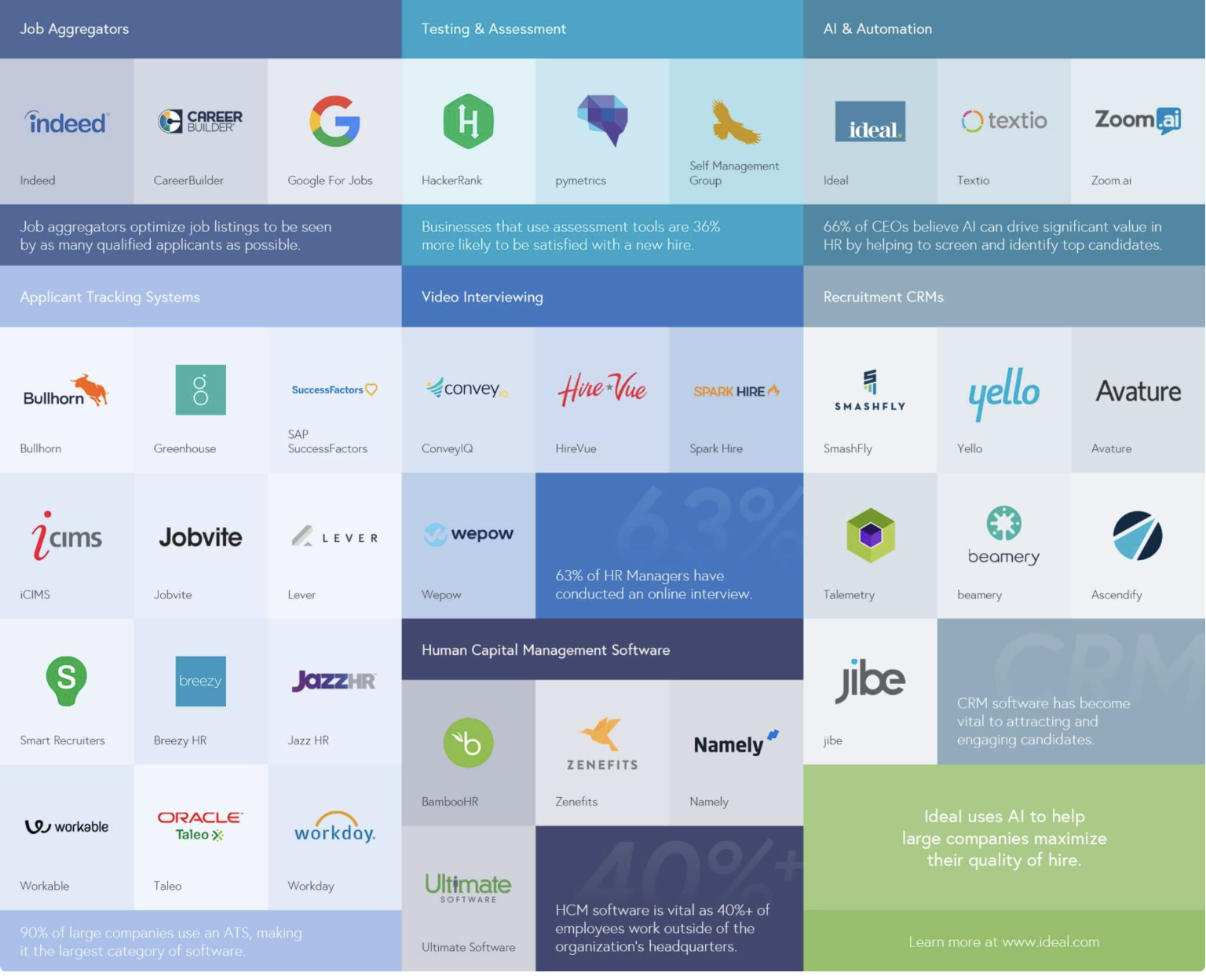

So, yes, there is still some search in search but truthfully, if you had the time to do it – and we know you don’t – you could likely unearth the approximate quality and quantity of names as we can. However, the true value add, and the reason I remain unconcerned by ZipRecruiter and the 37 other online recruiting tools out there, and the accompanying doom prophesied by my lunch companion many years ago, is that the real power of today’s executive search Jedi Master lies not solely in her ability to find the people but, critically, in telling that found person’s story. For we are no longer search professionals; we are professional story tellers.

The stories must, of course, be non-fiction but they must also be compelling and persuasive and meant to attract each side of the hiring equation to the other. No different, really, than setting up two strangers on a blind date. The broker of such a union must tell each party something about the other to compel them initially to even meet, and ultimately, hopefully, to consummate a meaningful relationship that lasts, well, at least the length of our guarantee period.

Which is why I find it so confounding that in executive search there remains a perceived supremacy associated with the capabilities of one firm over another based on nothing more than its search credentials. Though the old joke – What do you call the person who finishes dead last in their medical school class? Doctor. – is true, equally true is that the best organizations unfailingly hire people with the best grades from the best schools.

Indeed, Lauren Riviera, an assistant professor of management at Northwestern University, did a study about the hiring processes for top investment banks, law firms and management consulting firms in the US. Her conclusions? As a rule, these companies generally only hire from the “top 5” schools in the US (Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford and Wharton).

But there is no Bachelors in Recruitment Sciences and no standardized test like a GMAT or LSAT against which to establish admission criteria foretelling some harbinger of who will truly excel in executive search. There are no “top 5” schools from which the best search firms recruit. Every person in executive search is a refugee from some other profession, having sought asylum in search because its borders are open. Even realtors have to pass a licensing exam. But search people? They need to know how to dial a phone, use the internet and fog a mirror.

And, I submit, tell a story. And this is a truly unique skill that no standardized test can vet, or school can teach, or robot can replicate.

You see, at any given moment we are working with dozens of incredible company clients, every one of whom has an amazing story to sell, be it about their culture, their people, or their plans for the future. Innovative start-ups with proprietary technology; established multi-nationals with global opportunities; professional services firms with succession prospects; real estate development companies with enviable holdings and enormous growth plans.

So, too, do the people they desire to add to their teams have great stories to tell; about their work ethic, their drive, their team play, their desire. But these people are typically already doing these remarkable things for other amazing companies. Perhaps because they assume it to be self-evident or perhaps because as Canadians we simply aren’t wired to boast, in the end neither employers nor employees tend to do a superb job at telling their story and often the blind date fizzles.

Absent a catalyst to speed up the symbiotic reaction, it’s often just two impressive, though inert, people staring at each other, each wondering who’s buying and who’s selling. In order for the necessary reaction to happen there must be a means of accelerating the magic that, with respect, transcends the 5 step ZipRecruiter recipe of:

It’s absolutely not that simple. To suggest that’s all it takes is akin to describing flying a plane as:

And this is where the secret sauce of the great search firms resides. Not with the academic search credentials of the people they employ, for there are none, but with the facility of those people to be compelling, credible, articulate, authentic, persuasive, human story tellers. And the robots simply can’t do that. Need proof? Just ask Siri to tell you a story.

See, we’re successful because of the automation, not in spite of it. I was right those many years ago. We weren’t, and aren’t, doomed — like farmers and actors and construction workers and others are. Why? Because not the robots, the LinkedIn nor the Facebook will ever be as good at telling a story as we are.

Regards,

Adam