A few days after we opened the firm back in the fall of 2009, I summoned my then newest and first-ever employee, Ranju Shergill, into my office to shadow a call I was about to make to a target recruit. We had been given our first significant mandate; we were to lead the greenfield build of venerable Montreal law firm, Ogilvy Renault’s, Calgary headquarters. The mission that day was to find a tax partner. As a young lawyer, I had spent many hours sitting across the desk from senior partners watching them talk on the phone, hoping that by osmosis alone I could develop the skills I would need to one day function on my own. I chose to deploy this same cutting-edge training technique with my new charge.

I placed the phone on speaker, rolled up my sleeves and, like a surgeon scrubbing in, dialled. The target, an unsuspecting tax partner at a major firm, answered. “Still got it” I thought, giving away no hint of an expression lest my apprentice think this always happens. We made small talk, I transitioned seamlessly to the Ogilvy pitch, while the target listened respectfully. A few minutes later, like a Hulk Hogan leg drop, I concluded with my finishing move (the old assumptive close), and asked, “so, when might you be able to meet with my client to chat about this further?”

A short pause followed and then the target spoke. “Firstly, let me just say I’m flattered. But the truth is, I’m very happy where I am. I’m well paid. I enjoy my colleagues and I like my clients. My firm takes great care of me and my family and they’ve made a significant investment in my career and my future which I feel compelled to reciprocate with a show of loyalty. Thanks for your time but I’m just not interested in working anywhere else.”

And like that, the call ended.

The look in Ranju’s eyes said “how the hell am I going to make any money working here?”, followed by an audible “that didn’t go very well, did it?”. “Au contraire!” I protested, continuing, “what just happened there, happens 90% of the time in this business. Every successful recruit requires a ‘push’ and a ‘pull’; the latter is comprised of the opportunity presented by the destination, and the former is provided by something internal at the incumbent firm that would cause the candidate to leave.” My dissertation continued: “Think of it like two keys needed to unlock a door. All the pull in the world doesn’t change the fact that the tax lawyer had no push and he exercised his right to stay put. Good on his firm for creating the conditions that made him want to stay there. Now, who’s next on our list?”

If every person we called about a role said ‘yes’ on every call, every time, you’d all be recruiters. But not every employer is created equally. Some employers, many in fact, make it too easy for their people to say “yes” and then those employers blame us for asking the question. I tell my team all the time that it’s my job to create a working environment in which they’ll have long-term success; if someone else can coax them away to a better opportunity, that’s on me.

Here’s the point: the burden lies not with the suitor to refrain from making the advance; the burden lies squarely with the employer to create the conditions such that the target will easily decline that advance. My burden is to teach my kids how to cross the street safely; it’s not to contact every driver in my neighbourhood every morning to tell them to slow down.

Of course, it’s not quite that simple. Hot dogs are full of stuff. For starters, our Golden Rule is thou shalt not recruit from a client. Put another way, you shouldn’t foul your own nest. Seems easy enough but, you’ll note it’s our Golden Rule, not le Golden Rule. Many in our unregulated industry are less concerned about the pristine state of their nest. And what does ‘recruit’ mean? And who’s a ‘client’?

Let’s answer the easy part first. A client, at least the way we define it, is an organization to whom we have sent an invoice in the preceding 12 months. That’s fairly black and white.

Defining “recruiting” is a slightly greyer endeavour. For, one of the most effective means of finding talent is by leveraging the networks of the people who know the people you seek. And often those people work at clients. After all, it’s your clients, particularly your placed candidates at those clients, who know you best and it is those people who will be most willing to assist. But when are you legitimately sourcing someone at a client firm versus sneakily end-running the Rule by surreptitiously hoping they’ll bite on your entrée? We believe the answer is ‘never’; others believe the answer is ‘always’. So, when a legitimate sourcing call morphs into a “hey, I might know someone: me!” call, who’s at fault?

Thing is, if you want to find a great fragrance chemist, or a top-notch quilter or a leading elephant dresser, call other fragrance chemists, quilters and elephant dressers and ask them who they know. Closer to home, if you’re looking for a CEO of a 20,000 boe/d E&P company with expertise in the Permian, call other CEOs of similarly sized companies operating in a similar geography. And if you’re looking for a 2013 call to the bar corporate associate with M&A experience, cross-border transactional know-how and some private company familiarity, call other 2013 lawyers with similar experience. After all, they likely went to school together, went through the bar admission process together and go for beers after work and complain together. They know who’s happy and who’s not and they can usually lead us to the person who can lead us to the person who can lead us to The Person.

The problem is that while birds of a feather tend to flock together, when they do, the nest is more easily fouled.

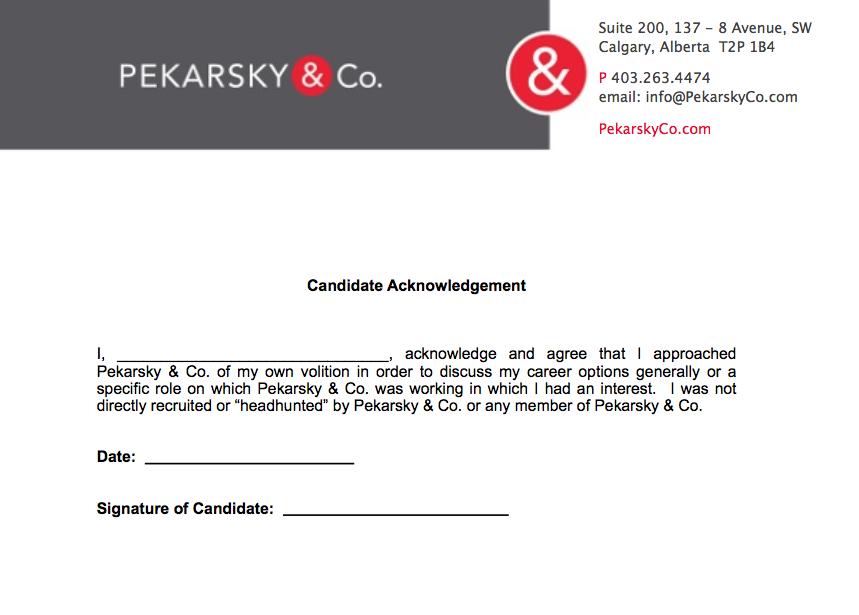

For this reason, whenever we source a contact at a client we have to be extremely careful and clear as to our intentions. Firstly, we make it very clear that our call is a confidential enquiry (more on that later). Second, we state expressly that we are not recruiting him or her, for he or she is a member of a client organization. Third, we are the only firm to use a Candidate Acknowledgement Form to cover ourselves when, as occasionally happens, someone from a client firm pays us a visit in search of a change. Still, we get our hand slapped.

You see, there’s a breed of employee who leverages any call from a recruiter to score points internally. Having received a genuine sourcing call from a recruiter, some employees will skip down the hall and make a point of telling everyone who’ll listen they got a call from a recr-uuuuuiiiter. As though it somehow (a) demonstrates they’re special and wanted; and (b) increases their internal loyalty quotient by leveraging that call into the self-serving, ingratiating storyline that they have, ipso facto, been recruited. Receiving a call from a recruiter no more means you’re being recruited than receiving a call from a doctor means you’re sick. Forget for a moment that our initial outreach was clearly couched as confidential and forget again that we actually weren’t recruiting that person. No matter. There’s a breed of client who simply refuses to believe that we could possibly be bona fide in our outreach. Like a game of broken telephone, by the time news reaches the desk of the person who signs off on our invoices, there are feathers flying everywhere and I’m left to clean the coop.

And here’s what the flapping wings of chickens coming home to roost looks like, as evidenced in this excerpted note I sent to one particularly aggrieved and disbelieving now former client:

I am 100% confident that our calls into your firm were, as I’m sure the voicemail indicated, seeking to tap into the network of people who might know people who could lead us to our ultimate candidate. As mentioned, it is absolutely not a solicitation of your people to call them and ask them who they know. If they interpret this as being directly headhunted, that’s on them, not us. Frankly, they shouldn’t flatter themselves. Moreover, to suggest that they would not otherwise have become aware of the opportunity but for our sourcing call is, in our view, a dated one. We have over 10,000 monthly hits to our website, our newsletter and our many social media properties. Our posts are swept by other job boards, forwarded by peers and tweeted, linked and disseminated through so many tools that if your people were unaware of those opportunities I would be worried about their ability to survive in the modern world.

We are extremely clear with our team that any calls into any firm should be handled on a purely sourcing basis only. There is no way that we could have successfully worked for 18 of the 30 largest law firms in Canada and over 75 of the Alberta Venture 250 companies in Alberta if we showed disregard for our community in the manner you suggest. If your people want to impress you by ‘ratting out’ a recruiter who made the very type of call that we made to hundreds of people on your behalf and to your benefit (none of whom, by the way, felt compelled to leverage our call for their own gain) then, again, it says more about your folks than it does mine. And if your people are going to be so smitten by a 15 second voicemail that they decide to uproot and change careers because of it, I would suggest those roots weren’t too deep to begin with.

Cluck cluck.

Why not just place a full embargo on calling into any client firm, you ask? Why not just bubble wrap your kids every morning before they head to the crosswalk? Because, aside from bona fide sourcing calls, we often call for a host of other non-sinister reasons, including reference checks, or volunteer Board positions or even to refer work to a firm. We’ll call into a firm where a client of that firm is seeking to bring someone in-house and we’ll ask management if they have any thoughts from amongst their own ranks as this can often be a win/win for both the company and the firm. And sometimes we actually even have friends at client firms who we like to call to just say ‘hi’ to. Honest!

And beyond calls, our newsletter is sent to thousands of readers, many of whom reside in client organizations. Some have even suggested our newsletter is merely a cleverly disguised end-run to place our “Featured Opportunities” in front of their people. I assure you, if that were the case, I’d save the cost of both time and energy it takes to write this newsletter and simply advertise our roles far and wide, as most of our competitors do to avoid this very situation. Indeed, recruitment firms that advertise heavily avoid this entirely. They simply blast the market with print ads and whoever applies, applies. That’s not hunting; it’s fishing. And, frankly, it doesn’t work very well. Lawyers are more risk averse than your average bear and the passive job seekers (as opposed to the active ones) simply won’t risk applying on-line or to a print advert not knowing who’s reading it and where it will ultimately end up. In an ironic twist, the market trusts us more than it trusts our clients.

But there’s another reason the full embargo doesn’t work. And that’s this: Employees resent it. Kim Jong Un might be able to convince his starving masses that their country is a world super power but even Managing Partners of law firms don’t possess that type of control over their subjects. One firm that asked us to place a full embargo on calling into it has, unbeknownst to it, created an angry backlash amongst its people who would like to be informed of what’s going on in the world when it comes to opportunity. They’ll decide what’s best for them, thank you very much. You can’t win for losing.

In the end, it all comes down to intent. Clients hire us to leverage our network by calling people who will lead us to people who will ultimately move to their organization. If it was as simple as running an ad, they’d do it themselves. If it worked every time, you’d all do it. It isn’t and it doesn’t so everyone needs to focus their energy on making their place of work the best possible place to work; until then, the free market will work the way it works. And we did just win the Canadian Lawyer Readers’ Choice Award so I’d suggest it’s working just fine.

And you know what else? Hot dogs taste good.

Regards,

Adam